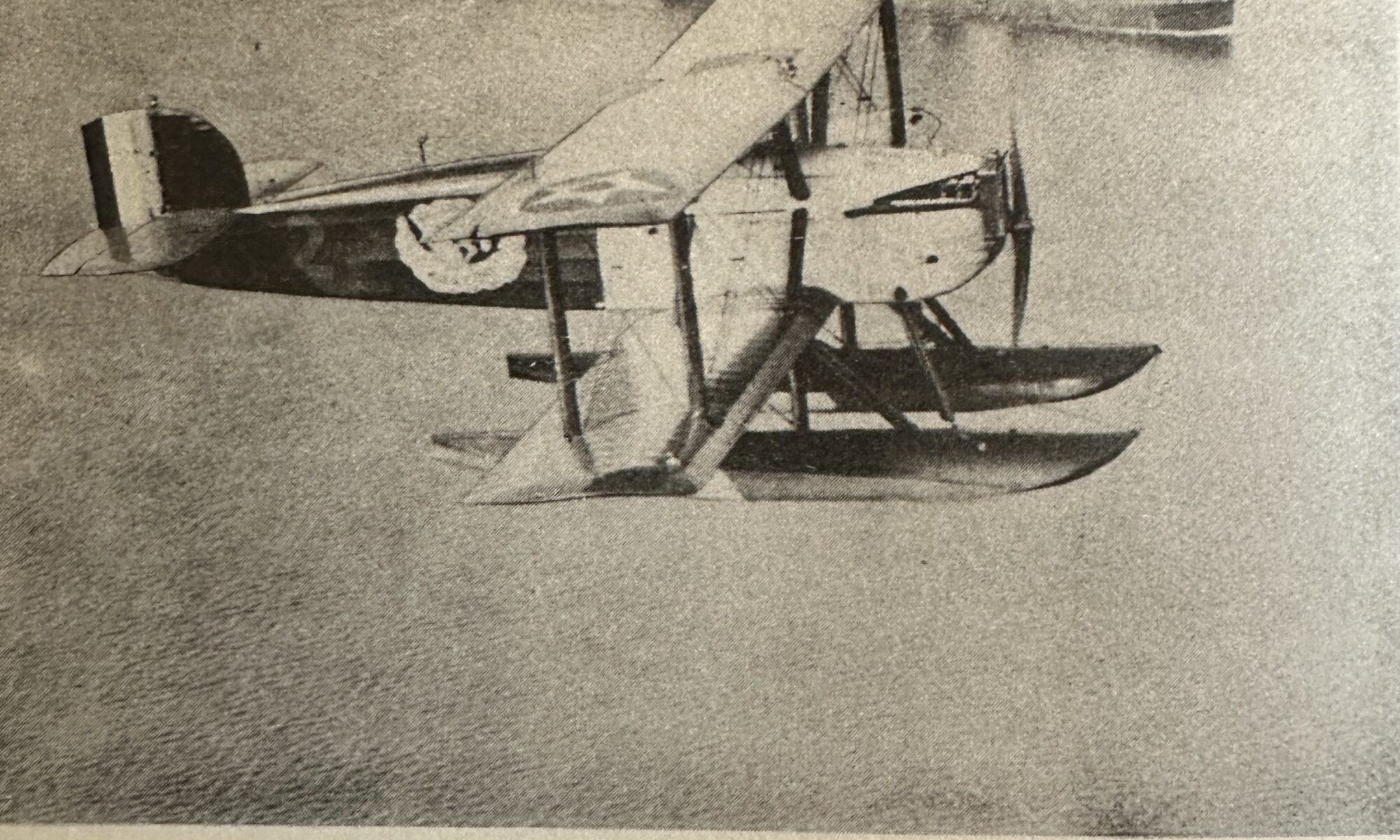

While it’s not quite in the same league as later journeys spanning our largest ocean, the flight of three Douglas World Cruisers that made it to Kagoshima, Japan, in May 1924 marked the first time the Pacific Ocean had been breached by air. By hopscotching up the Aleutian chain and over the Bering Strait, they plied their way—the Chicago, the New Orleans, and the Boston.

And they had to stay out of Russian waters along the way. Intrepid Russian officers paddled out to give them a jug of vodka, however, as they rested on May 15, bobbing in the waves well outside the three-mile limit off shore, according to Sky Master.

When they made their way into Japan’s Kagoshima port, crowds waited on the sand to cheer their arrival. By May 17, headlines filled the newspapers back home, in time for the Saturday editions.

On May 24, the DWC crews went to Tokyo (spelled “Tokio” in Sky Master) to attend a grand reception. It would foreshadow the future, in the Sky Master text, which was published in 1943. Wrote Frank Cunningham: “The sight of American planes, though, upset the Japanese as they realized that even if the world flight planes were friendly ships, the United States might be able to fly fighting planes to Japan. Some writers have stated that the visit of the DWC planes gave aviation a tremendous impetus in the kingdom of the Rising Sun.

“The Evening News of Shanghai, China, May 23, reported an Eastern News Agency dispatch from Tokio saying: ‘The enthusiasm with which the American round-the-world-fliers were welcomed by the Japanese citizens when they safely arrived at Kasumagira [sic] well illustrates the Japanese good will and friendly feeling toward the United States despite the existence of the present Japanese-American controversy over the immigration question. [The U.S. had just passed the Immigration Act of 1924, effectively ending immigration by Japanese at the time.] Tokio today with the whole Japanese nation enthusiastically is fêting and giving welcome to the American airmen.'”

![At the Daher booth in the Career Fair, we learn how to cleco a rivet. [Credit: Julie Boatman]](https://julietbravofoxmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_3516-1024x768.jpeg)