Back in 2019, we made a pilgrimage to the beaches of Normandy to join aviation enthusiasts and family in the commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the D-Day invasion. Part of my remit then was to cover the events both in France and England for Flying magazine.

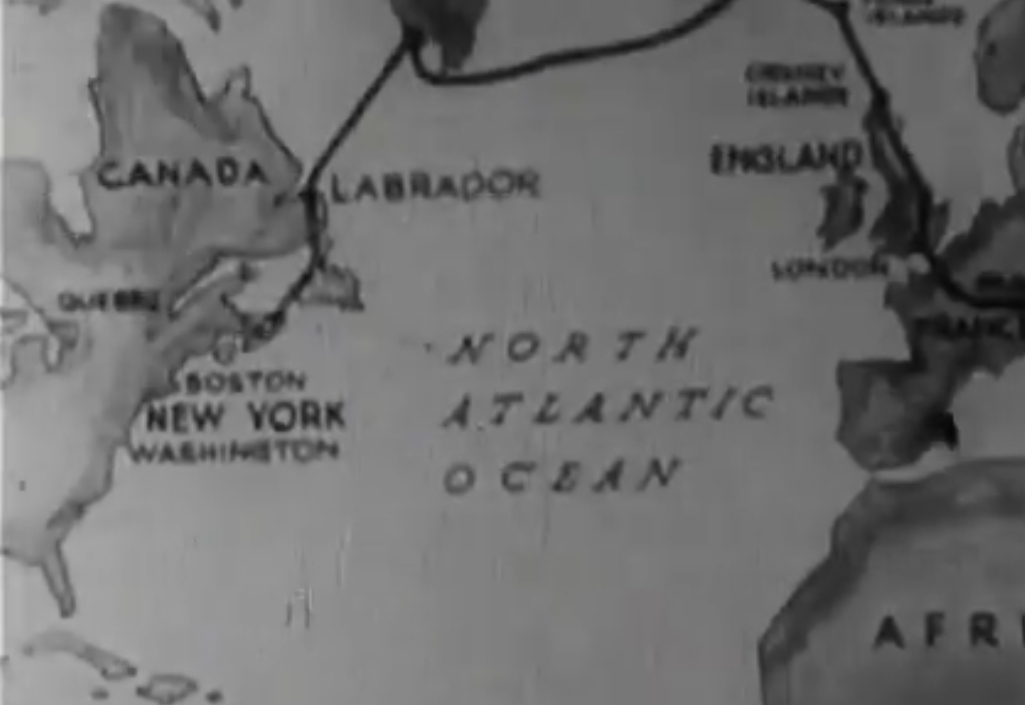

But more importantly, I had the privilege of interviewing and flying with members of the D-Day Squadron, the collective of which had just flown a coterie of Douglas DC-3 and C-47 variants across the North Atlantic to be part of the memorial displays. Back then, the group formed in coordination and with the support of the Tunison Foundation, which at that time operated Placid Lassie, a restored C-47. The foundation made it logistically possible for Placid Lassie to make not only the crossing but also keep to a busy schedule of events and airshows throughout that year and beyond.

Following that incredible year, the DC-3 Society was born, with a mission to create a true stewardship for the DC-3 type, with a charge to educate, support, and maintain the flying Douglas DC-3s and their extensive model series into the future. With an estimated 150 DC-3s and variants still flying, that’s an important pursuit.

Now, on the 89th anniversary of the DC-3’s first flight in 1935 in Santa Monica, the D-Day Squadron is poised to make a solo flight of its own. With a nod of thanks to the foundation, as of January 2025, the Squadron will stand separately, ready to carry on the mission.

Eric Zipkin, board president of the Tunison Foundation, served as chief pilot for the 2019 and 2024 D-Day Squadron missions to Normandy. “We’re excited for the future of the DC-3 Society, especially continuing to operate this type of aircraft in our current climate,” Zipkin said in a release. “It’s imperative we have a structured member organization looking out for our best interests and needs.”

The DC-3 Society will continue to be led by executive director Lyndse Costabile, and its standalone 501(c)3 status will soon be official. The Society will focus on the Squadron’s programming and platforms, while the Squadron will focus on flying displays commemorating the DC-3. “We know the D-Day Squadron is globally recognized, that’s no secret,” said Costabile. “It’s become a symbol to many in celebrating the Grand Dame, the legendary DC-3 and all those who crewed and maintained her.”

“That is why we must highlight the DC-3 Society to ensure longevity of our programs, membership resources and continuing to celebrate all that the DC-3 has accomplished in war and in peace,” Costabile added. Those programs include a favorite of mine, the Young Historians, which encourages the next generation to study and understand the airplane and the extensive role it has played in global history, from its airline days, to World War II, to the Vietnam War, and to the present day in cargo and transport operations.

“We know with the DC-3 Society there is a place for our younger generation to help tell the stories of the Greatest Generation, our heroes too humble to even consider themselves heroes, ” said Henry Simpson, pilot and founding member of the Young Historian’s Program based in the UK. “I am looking forward to our role to help lead the society’s education and outreach programming, continuing our mission to serve, honor and pay tribute to veterans.”

We’re here to fully support the next mission, which includes a string of 90th anniversary events across the U.S. and Europe in 2025. Want to join in? Follow the DC-3 Society website and social channels.