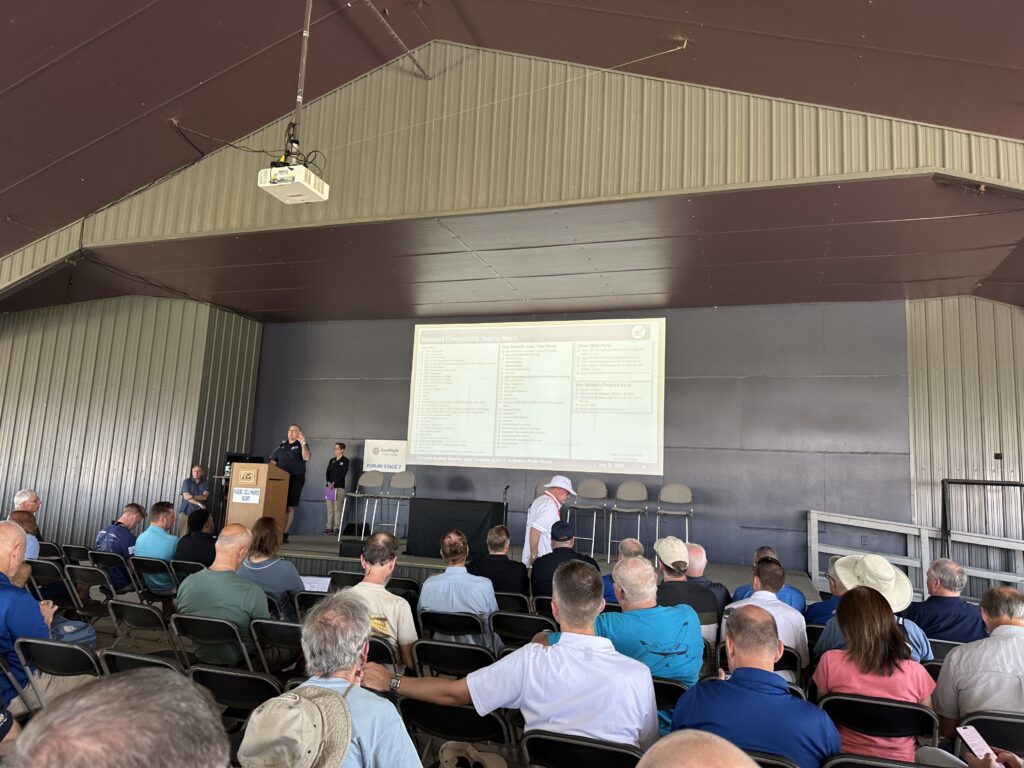

While a record number of folks flew in to Oshkosh, the forum wasn’t quite full for the EAGLE (Eliminate Aviation Gas Lead Emissions) briefing at 10 am on Monday, July 22. But a couple hundred interested parties (pilots) did show up—and they were in for quite a review, punctuated by events unfolding throughout the week at EAA AirVenture. To review, EAGLE’s goal is to eliminate the use of leaded fuels in piston-powered aircraft in the U.S. by the end of 2030.

In the briefing, the FAA and industry consortium put representatives up on the forum stage, including co-chairs Curt Castagna, of the National Air Transportation Association (NATA), and Wes Mooty, acting administrator on certification for the FAA. Walter Desrosier, GAMA’s technical lead on fuels, presented as well.

Desrosier gave an in-depth look at where each of the candidate fuels are on the path to the marketplace. But even the “big picture” simplified version of that path appeared more complex than has been perhaps sold to constituents.

Three candidate fuels remain in the mix:

* GAMI’s G100UL, which has an STC but no ASTM specification acceptance

* Swift’s 100R, which is undergoing concurrent STC and ASTM compliance testing

* LyondellBasell Industries’ UL100E, going through the Piston Engine Aviation Fuels Initiative (PAFI) program, which progresses towards ASTM acceptance and fleet authorization

After compliance is unlocked, the stakeholders in the supply chain must accept it along the way: aircraft and engine OEMs, fuel distributors, FBOs, aircraft owners/operators, and pilots.

Dan Pourreau, of LyondellBasell Industries, maker of UL100E currently going through the PAFI process, led a separate presentation later in the week. In it, he noted that a true drop-in replacement for 100LL was quickly passing from reality. One reason? The MON (mean octane number) of 100LL with which many high-compression engines were certificated is roughly 104, and may be as high as 106.

The best that unleaded fuel can do with non-lead boosters has been around 100 MON. That means that if an engine cannot accept the 100 MON, it may need mods to its operating conditions, such as cylinder head temperature limitations (“paper mods”), or further mechanical or technical mods.

Materials Testing?

There’s another concern raising a specter over the viability of GAMI’s fuel in particular. And that has to do with the materials testing that earlier candidate fuels in the PAFI program failed to pass. When you put fuel into the wing of an airplane, you pump it into a tank and start its journey through a system that includes elastomers (O-rings, hoses), metals, rubbers and other bladder materials, plastics, sealants, and paint. You have the certified fleet to consider when walking through the potential interactions—and then there’s the experimental fleet.

During Desrosier’s presentation, he popped up a Materials Compatibility Testing Matrix slide listing an outline of the materials that EAA has put forward through the EAGLE consortium for consideration in the process of ensuring a candidate fuel won’t negatively interact with anything it comes into regular contact with. While the OEM holds responsibility for testing certified aircraft (including its legacy models), the individual builder must test their own.

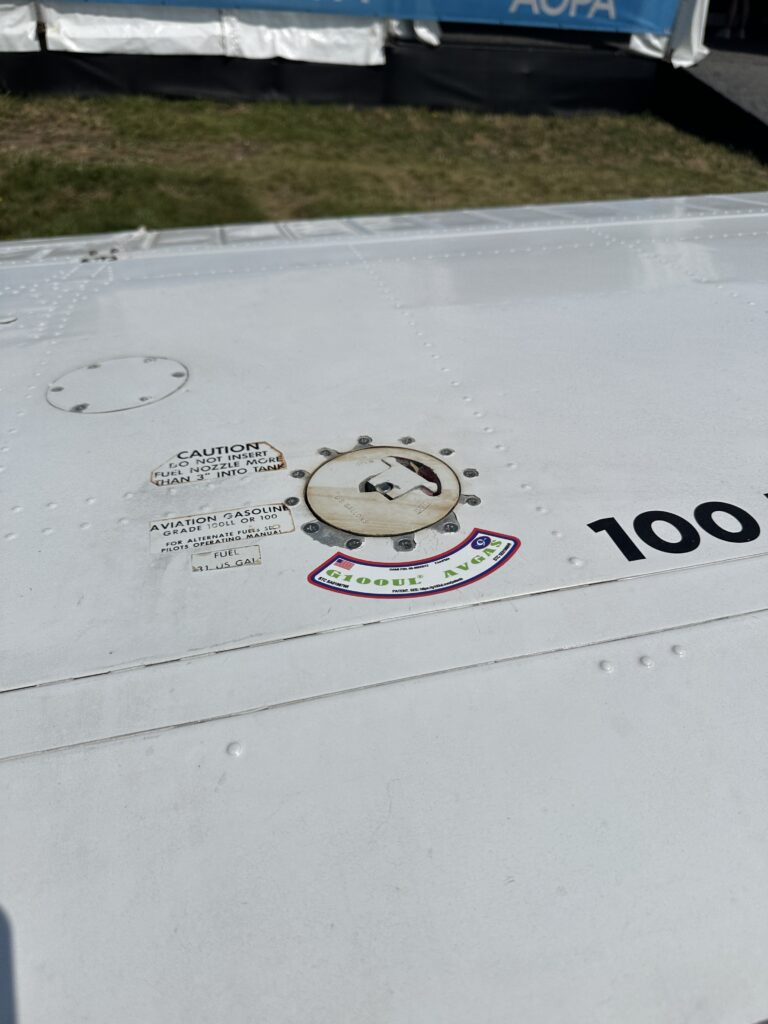

So, one of the 2,846 showplanes on EAA’s display last week drew my interest as a result of this question: the Beechcraft Baron that the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) is using to demonstrate to its members the high-octane unleaded fuels vying to replace 100LL. I’d have reason to take a close look at it as the week wore on—Oshkosh often serves as a proving ground for new designs and technologies, in that they must sit out in the sun, wind, and storms for more than a week in many cases. That’ll test anyone’s material makeup.

AOPA flew the Baron to the show with GAMI’s fuel powering the left engine. As the week wore on, two things raised questions in the area of materials compatibility—though nothing is conclusive yet. The first one feels perhaps cosmetic: the stain growing on and around the fuel cap on the left main tank where white paint had been previously.

The second one feels more onerous, though we don’t yet know what the cause is. A line of oil-colored sludge reeking vaguely of sealant seeped from the seams underneath the wing, at low points near where the tank sits inside the wing. I crawled under to take a look myself, and it was there for all to see. Until the source of the sludge is inspected, however, its origin is inconclusive. Stay tuned for more as other results of long-term testing/demonstrations come to light.

We Have a Mixing Problem

The FAA recently published data that indicates GAMI’s fuel uses m-toluidine, an aromatic amine, as an octane booster. Not only does this set of chemicals potentially pose materials compatibility problems, but it also raise the problem of intermixing in the field—or within a tank. For its part, Swift Fuels has stated that any fuels containing aromatic amines cannot be intermixed with any Swift Fuel, including the 100R.

LyondellBasell reported that its fuel will be fully miscible with 100LL, since it runs very close to the leaded fuel in its chemical and physical properties. But it too is not likely to be mixable with either GAMI’s or Swift’s fuels.

And that prompted me to ask the question at the forum, is there a point at which the FAA and industry will need to get behind one fuel to move forward with—especially since FBOs are unlikely to have multiple tanks to dedicate to unleaded fuels? The market is so small as it is, and the risk of bifurcating it into two or three high octane unleaded fuels doesn’t sit well.

With these clouds on the horizon, the race to field a workable unleaded fuel solution for the GA fleet by 2030 has only intensified. The next EAGLE report will be virtual, in October. I plan to be there—will you?