The replica of the Seattle—one of the Douglas World Cruisers that did not complete the round-the-world flight—embodies the passion project of one man who by force of will recreated a dream that we honor this summer on the centennial of that milestone mission.

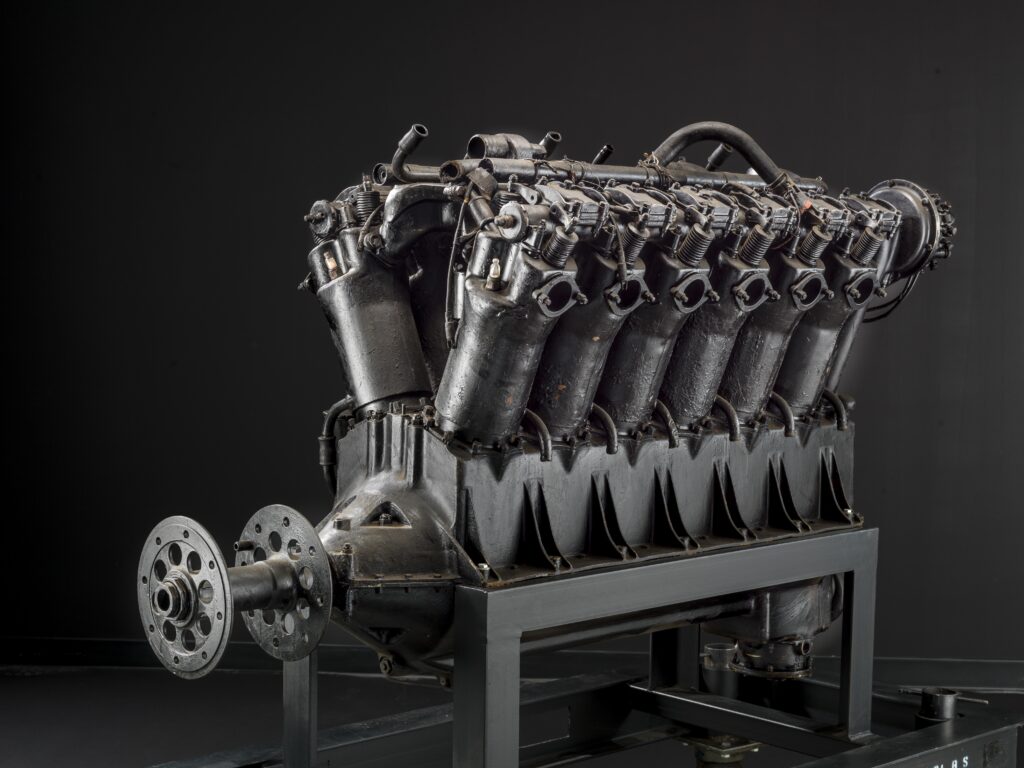

The Seattle II, built by Robert “Bob” Dempster and his wife and fellow pilot Diane—and a list of various contributors since 2001—sounded its Liberty V-12 engine for the final time on June 8, at the Chehalis-Centralia Airport in Washington.

I received a card invitation in the mail and wanted to fly across the country to hear that roar, knowing how precious it is becoming to witness the powerplants of yore in action. They may all be transformed to burn Jet-A or SAF or whirr on electricity in a shorter timeframe than we realize.

But alas, circumstances conspired, and so a friend of mine also with a passion for aviation history, Meg Godlewski, attended. I asked her to bear witness in my stead—and to snap a few pics off her iPhone. I give you this gallery and a tip of the hat to Bob, who I first met in October 2020 when the Seattle II was still barely kept under cover at the Renton Municipal Airport. It was still on floats, so it stretched amazingly tall in its open hangar home.

The Dempsters intended to fly the Seattle II around the world this year. After a spate of flying (including Alaska and Texas, and a commemoration flight for Boeing’s centennial in 2016), they settled for one mighty roar in 2024—and a permanent home at the Museum of Flight.

Sometimes life works out that way.