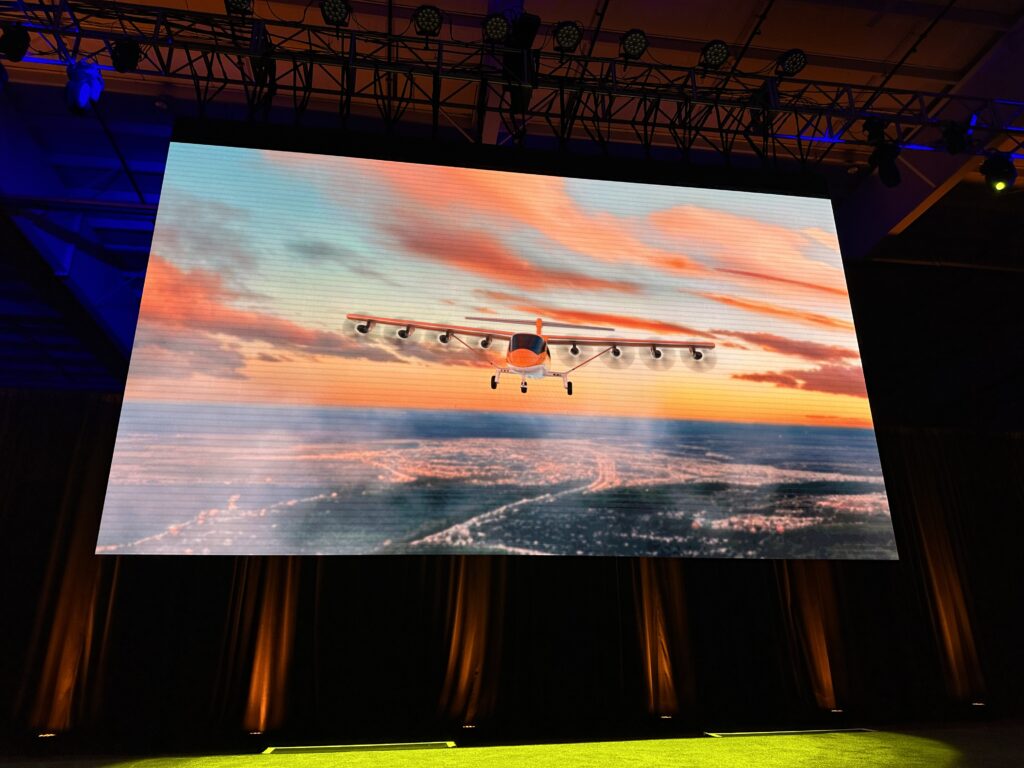

For my friends catching up, Electra Aero is a very cool aviation start-up that proposes a niche vehicle in the short- to medium-haul regional transport scheme. It ain’t eVTOL… it’s eSTOL, and it uses current airplane and pilot certification bases to achieve a new meaning for short-field takeoffs and landings.

On Wednesday, November 13, Electra Aero in Manassas revealed the EL9 Ultra Short model at its development hangar at KHEF. I was last here for the unveiling of the two-seat technology demonstrator a year and a half ago, and I would not have missed being here for the unveiling we heard announced at NBAA-BACE 24 in Las Vegas last month.

The EL-2 technology demonstrator shown alongside the coming 9-seat prototype has been making aviation over Virginia skies (and elsewhere) proving the concept—and resulting in takeoffs and landings of less than 150 feet. That’s critical for launch customers like AFWERX and other military and civilian regional transportation applications.

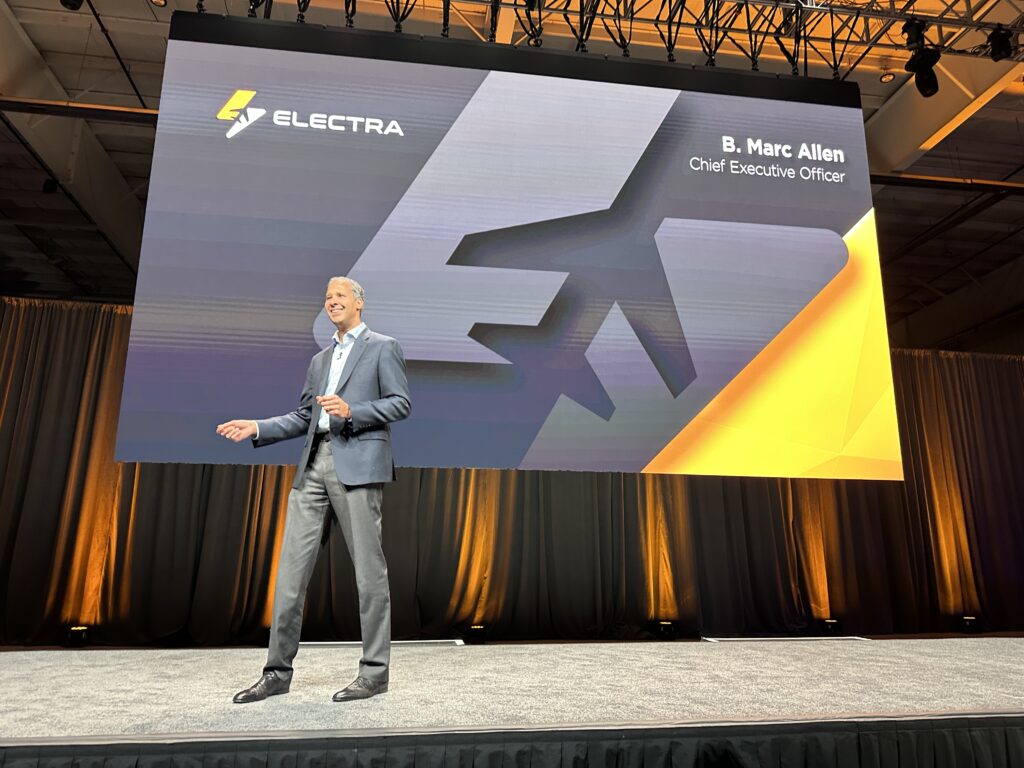

With a nod to aviation visionary and Electra founder John Langford, CEO B. Marc Allen and SVP JP Stewart talked the audience through the technologies within the future EL9 that leverage the advantages of hybrid-electric motors over purely jet-A driven ones. The EL-2 Goldfinch has been demonstrating these elements for the past year since its first flight in November 2023.

Buddy Sessoms, chief engineer from Electra, walked through the flight test program thus far, and the three enabling technologies at its core:

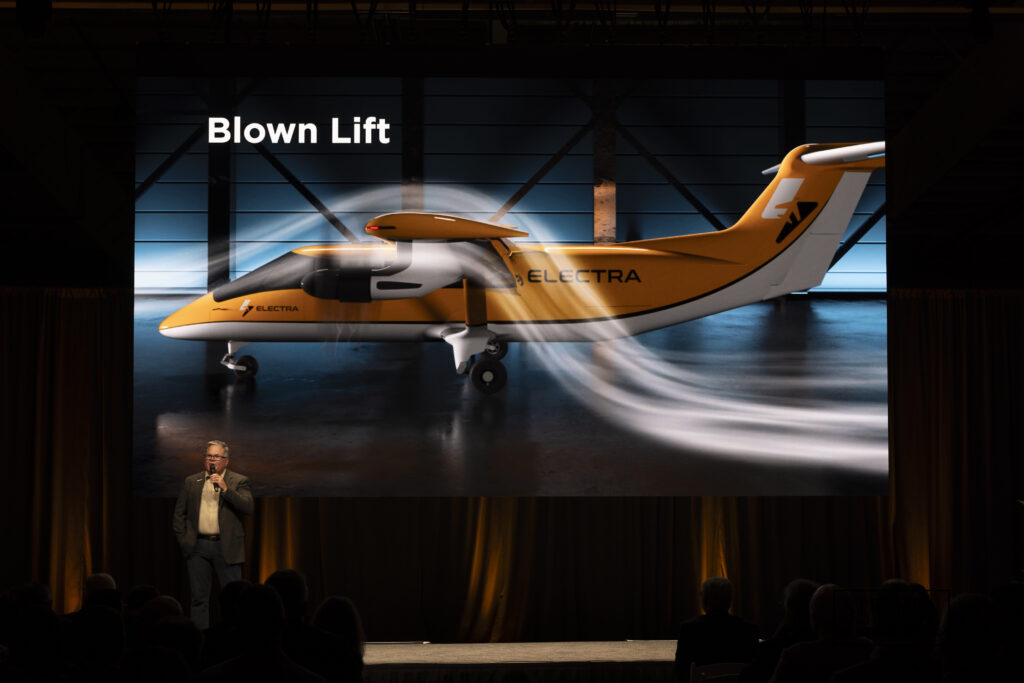

- Blown lift

- Distributed hybrid-electric power (DEP)

- Fly-by-wire (FBW)

The trio come together in a way not possible before—and are anticipated to enter service on the EL9 in 2029, making possible direct travel beyond helicopters, jets, and turboprops. For example, the blown lift enables flight at such low airspeeds to reduce the takeoff and landing distance to that of a typical runway centerline stripe.

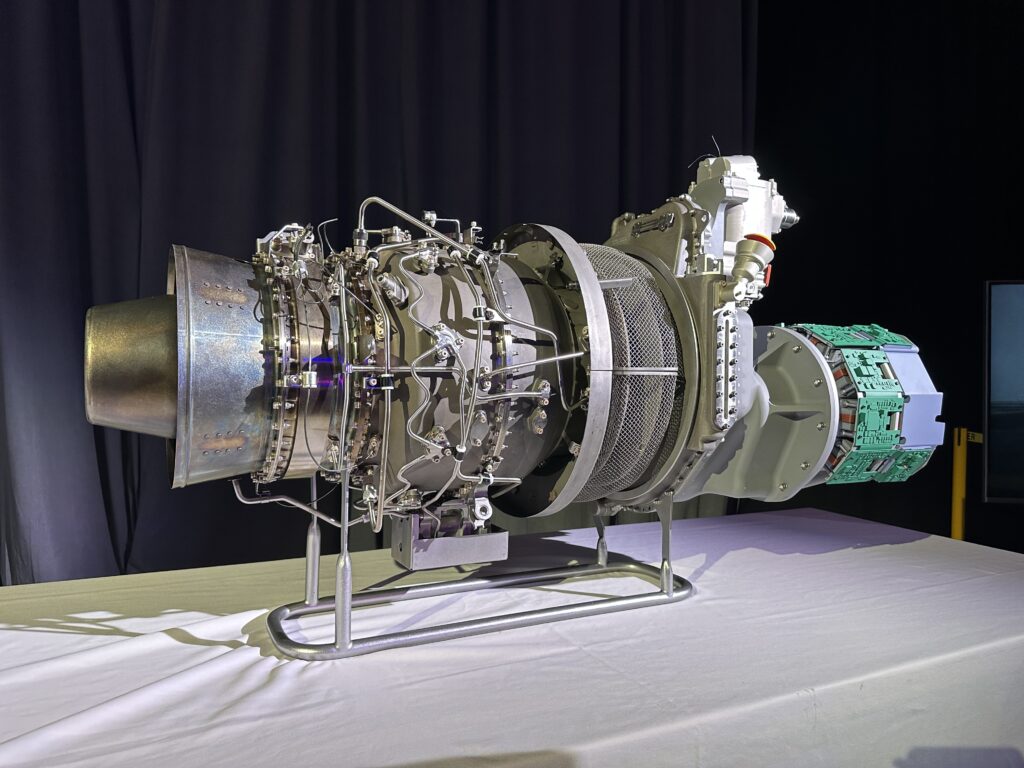

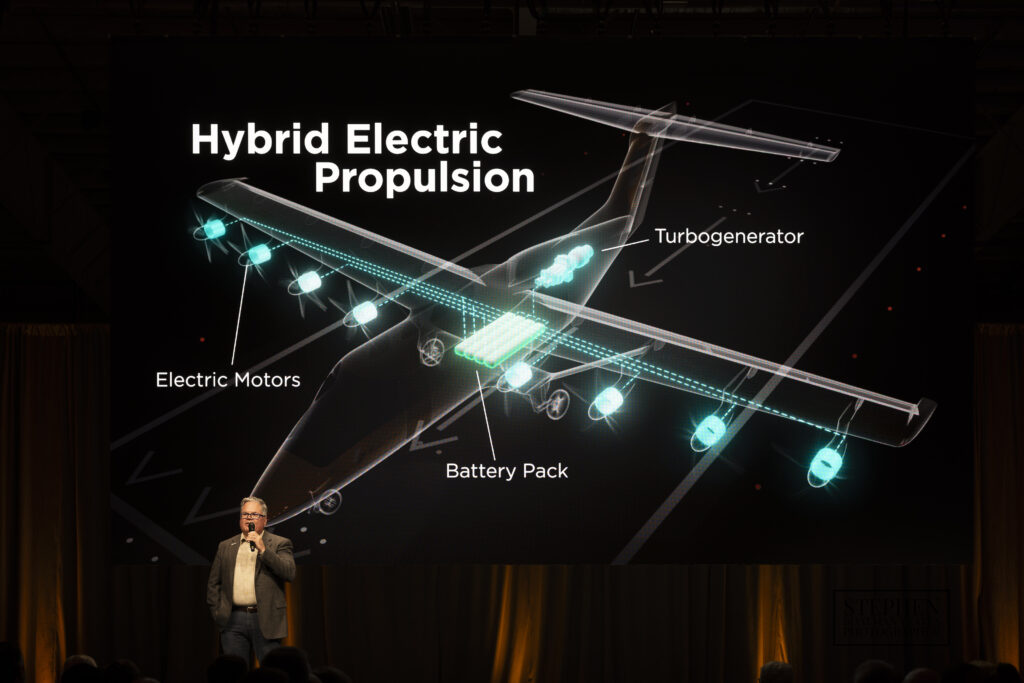

Distributed hybrid-electric power, or DEP, has been made possible by the lightweight Safran turbogenerators, designed such that 8 can be placed across the leading edge of the wing. By using a combination of currently available sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) and battery power, the EL9 is projected to leverage the torque of the electric power with the long range and speed made possible by low-to-no-emission SAF.

And FBW? It orchestrates the blown lift and distributed power into action. “One motor fails, and automatically we shut down the opposing motor,” said Sessoms. “This leaves six remaining motors for safe flight. This is an unprecedented level of automation that is safety focused.” On a typical takeoff, the automated systems currently detect faults with minimal pilot workload. Plus, the pilot actuates this through a single throttle lever to control eight motors in concert, at all times.

“It couldn’t be safer nor simpler,” Sessoms concluded.

The unveiling revealed a full size mockup of the cabin and cargo area… it can be configured either way. Planning for a 34-inch seat pitch and the cabin 60 inches across and 58 inches high.

We have to wait to see the actual airplane, which will go into production shortly.

So, what are the hurdles? Similar to those of other similar-sized (9-seat single-engine turboprops and light jets come to mind), even the relatively modest amount of electric power needed to make a hybrid system work at this equivalent horsepower still requires management that is quite different from the shielding and distribution currently in use in traditionally powered airplanes.

In any event, the team appears energized to the challenge—and the target niche now occupied by the Cessna Caravan or Daher Kodiak gives plenty of use cases for a real product. We’re looking forward to seeing the EL9 fly into the future with much of technology—and infrastructure—available today.