March 17, 1924, marked a St. Patrick’s Day to remember for the Scottish Douglas clan of Southern California.

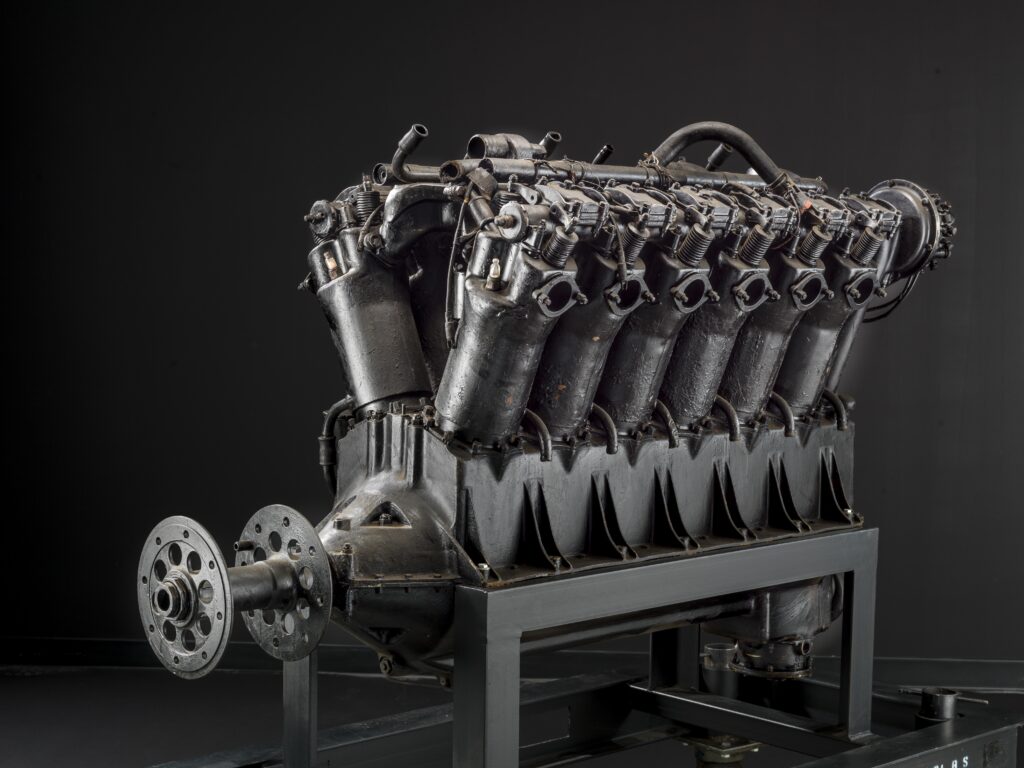

While recovering from the illness that had barred him from attending the events surrounding the impending departure of the Douglas World Cruisers, Donald Douglas surely smiled at least a little bit. For his ambition to grow the Douglas Aircraft Company by means of incredible feats of aviation history were about to take flight.

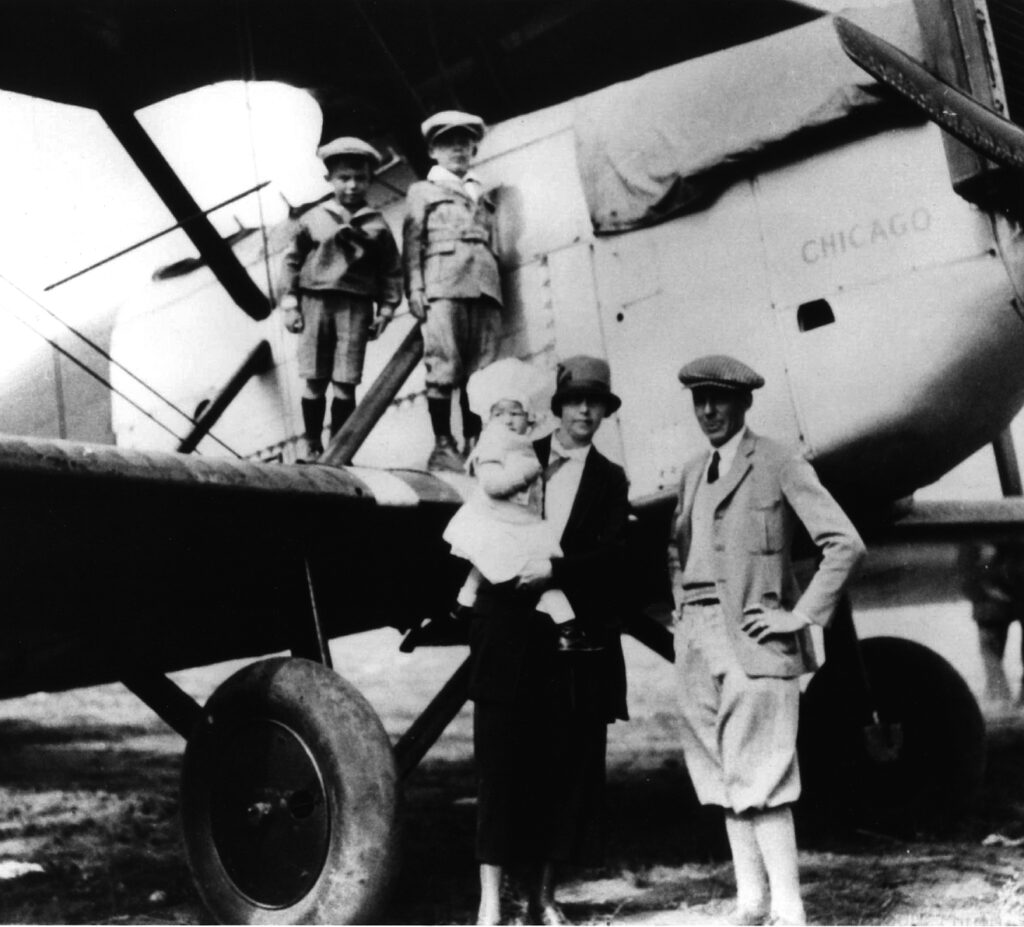

Robert Arnold, grandson of Douglas and Gen. Henry “Hap” Arnold, recalled his mother Barbara’s memory of her own grandmother’s recollection of the occasion. “Granny [Arnold came] up for some of these events from San Diego, and during one of them, Hap put her in the back seat of [one of] the World Cruiser[s] and took her up for a spin. And Granny was about 4 foot 10 inches and always wore big hats, and always a charming and, for her time, a highly educated woman.”

“Doug” watched the send off in a checkered cap and horn-rimmed glasses, striving to look the part of the nonchalant man-of-the-world he strove to be.

On the morning of the grand departure, the airplanes stood ready to go, but fog blanketed Clover Field. After a two-hour delay, three of Cruisers lifted off. It was 9:30 a.m., according to “Sky Master.”

What about the fourth? Lt. Nelson’s airplane, Ship Number Four, the New Orleans, sat in San Diego, only just completed the day before. Nelson made his way up the coast solo to join his compatriots in Seattle.