With the report from Daher, Safran, and Airbus on the Eco-Pulse hybrid-electric TBM-inflected tech demonstrator, the collective teams have the opportunity to stay future-forward—and incorporate lessons learned. In the interest of meeting the industry’s sustainable aviation objectives, we all have a vested interest in these outcomes.

A media briefing preceded the LinkedIn liverstream on December 10, from Tarbes, France. Leaders from each company—including Pascal Laguerre, CTO of Daher; Éric Dalbiès, SEVP of strategy/CTO of Safran; and Jean-Baptiste Manchette, head of propulsion of tomorrow from Airbus—joined project lead and head of aircraft design Christophe Robin from Daher. Over the past five years since the project debuted at Paris Air Show in 2019, I’ve stayed in touch with Robin on its progress, which will inform the way forward for all three companies.

What Is Eco-Pulse?

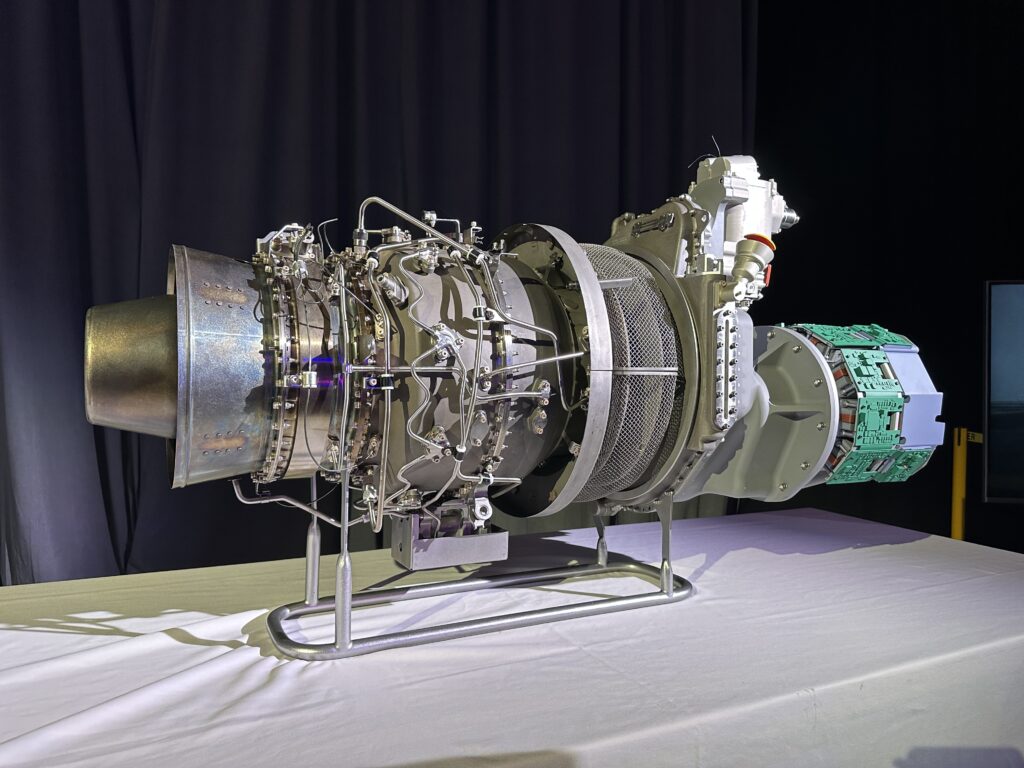

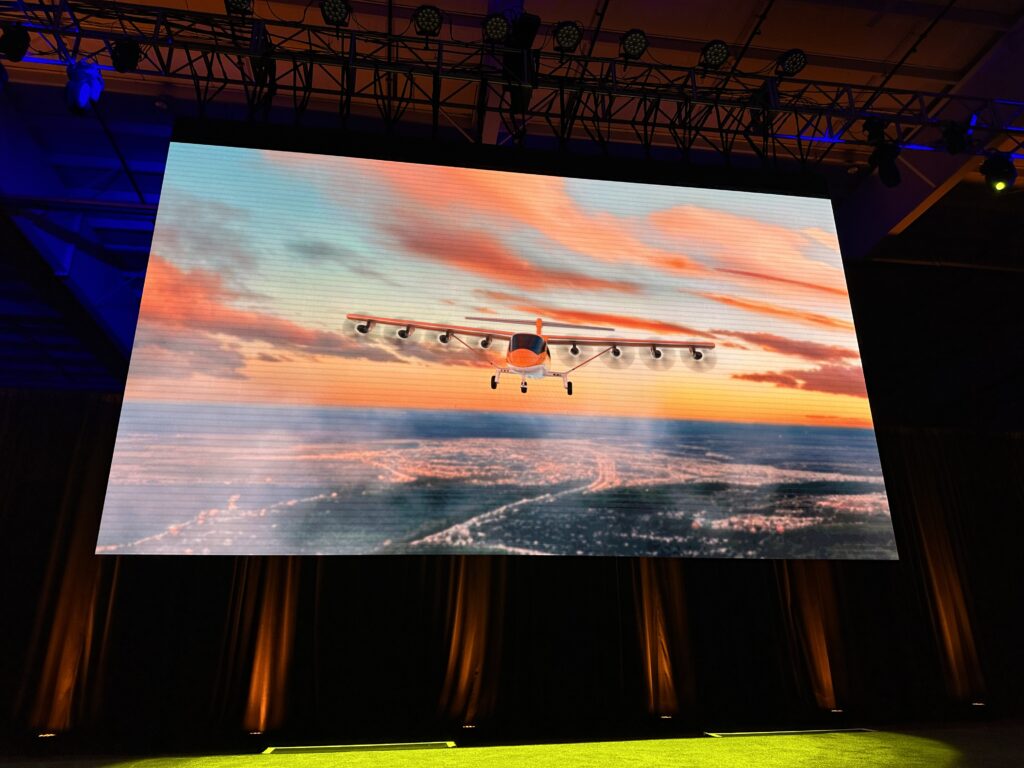

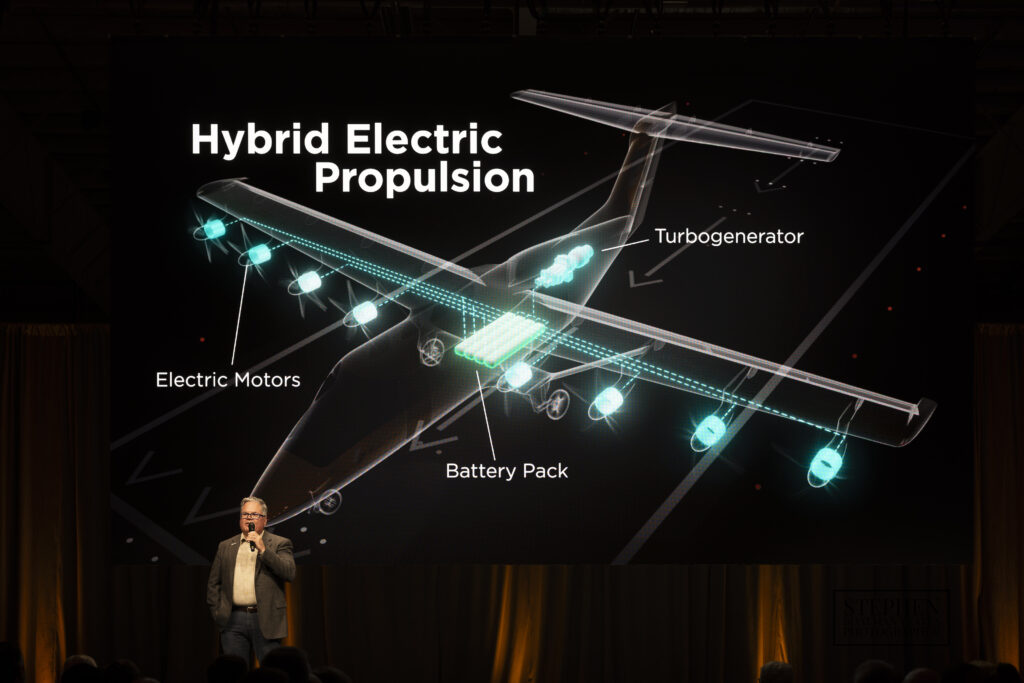

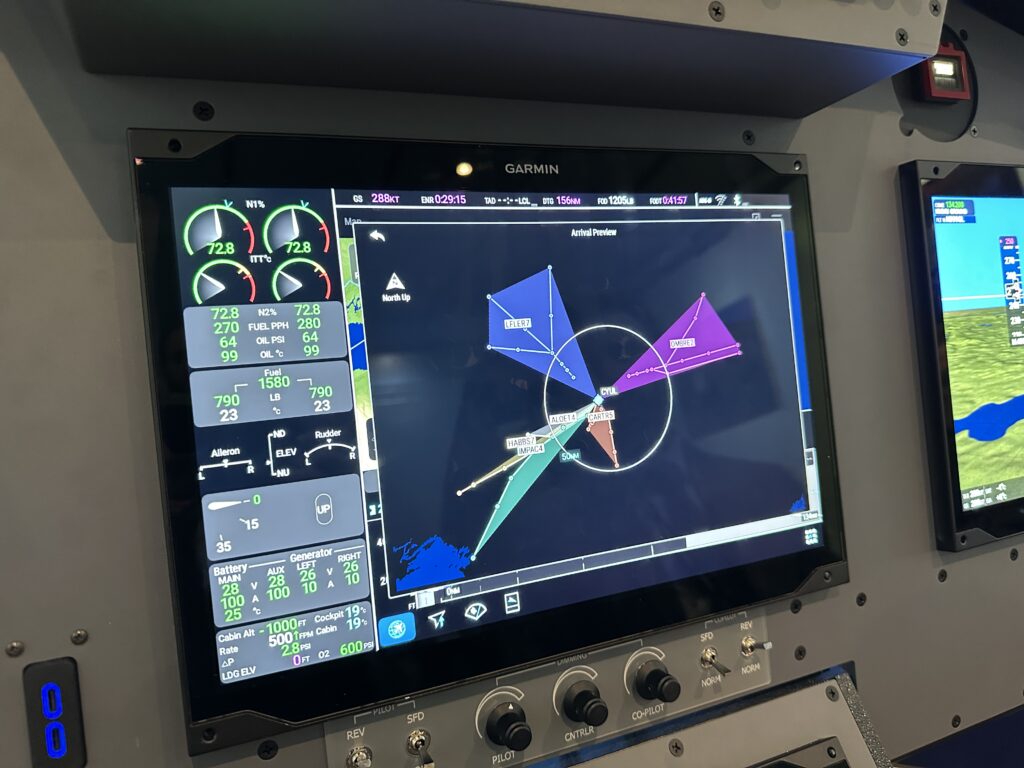

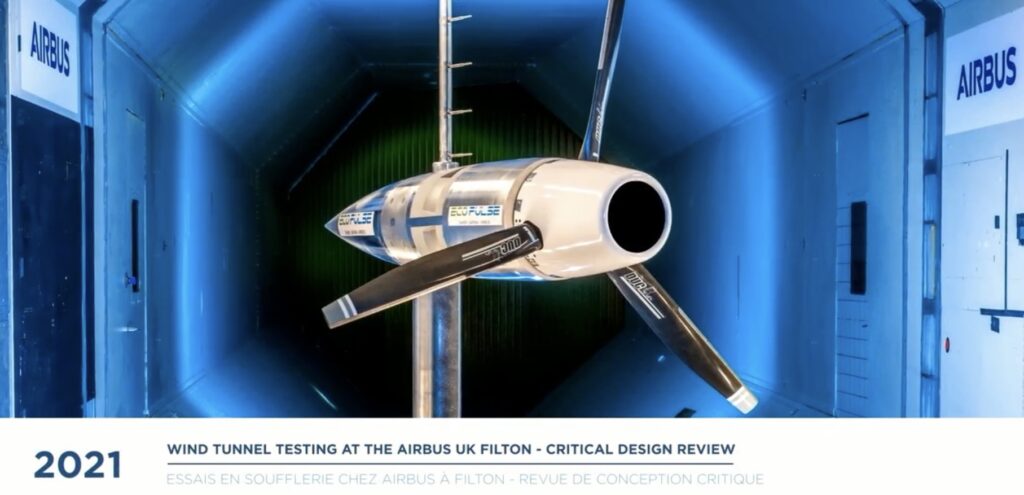

The Eco-Pulse project is critical for these leaders among aerospace OEMs because hybrid-electric propulsion forms a bridge between current jet-A (sustainable aviation fuel) burning turbine engines and full-scale electric propulsion. The aircraft at its heart is a technology demonstrator, in which a standard Pratt & Whitney PT6 turboprop engine remains in place on a tried-and-tested Daher TBM 900-series airframe. It’s joined by six Safran ePropellers on the wings integrated with a Safran-built turbogenerator and Airbus’ high-voltage battery pack (at 800 volts DC and up to 350 kW of power). A power distribution and rectification unit (PDRU) protects the high voltage network and distributes power via high-voltage supply harnesses.

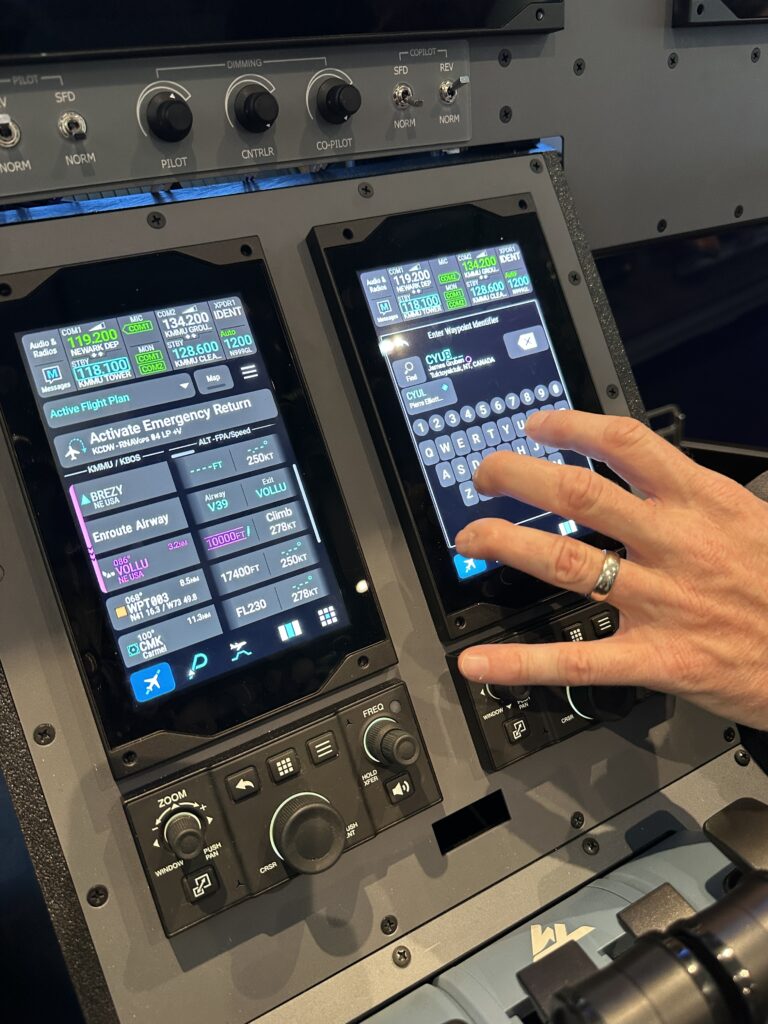

The pilot can use the six motors propelling distributed lift over the wing via a unified joystick-style flight control, via the integrated flight deck. It’s a unique marriage of tech dreams and true life—the Eco-Pulse project allowed for demonstration of these technologies within the envelope of safety required by the simple fact it was taking flight in the real world, not a simulation.

Flying it remains key to showing the operational safety necessary to move forward.

Flight Testing the Eco-Pulse

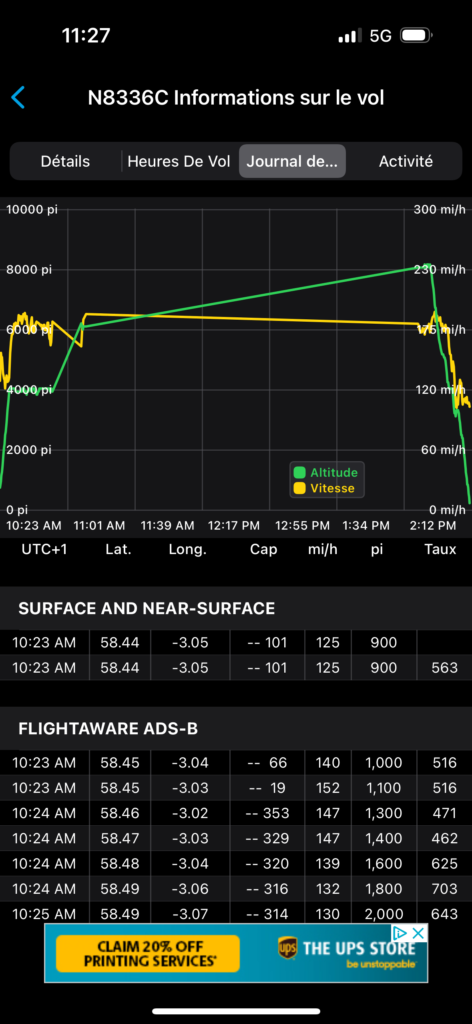

In the livestream, the flight test team described the progressive activation of the ePropellers and the eventually complete electrical actuation of the airframe and powertrain. During flight test, most of the hours of electric flight were conducted with the PT6 in “transparent” mode—not producing power, but not completely shut down.

Each step provided data to the respective companies, building on successive knowledge. For example, much was learned by flying the aircraft under its fly-by-wire (FBW) system, and under speed constraints. Stalls as well as the top speed of the demonstrator (190 kts) were explored. Slower airspeeds—as opposed to high-speed flight—provided some of the richest data, as the effect of the distributed lift caused by the ePropellers showed up most with lower in-flight airflow.

“You can imagine when when you have this propeller on the wing,” said Robin in the briefing. “The behavior is really different—you ‘blow’ the wing so the efficiency of the wing is completely different, thanks to the blowing effect of these six propellers. You increase the performance at takeoff, [and] during some maneuvers, and you can play with the flight controls, playing with the different[ial] power of these six engines. By doing that, you can play with the trajectory of the aircraft.”

Since the first hybrid-electric test flight on November 29, 2023, the Eco-Pulse has logged more than 100 hours in 50 flights, during which the team also noted other performance improvements, as well as the ability to reduce cabin noise with synchronization of the six propellers.

Unexpected Lessons: A Lot of Power

Two key learnings included a big challenge—managing the 800 VDC battery and the harness that distributes the power—as well as understanding how it will be maintained and serviced in real-world conditions. Things are just different in the air: A battery fire, for one, is more complicated than in ground-based vehicles, and because of the presence of the traditional turboprop engine, that fire may occur in close proximity to the fuel system.

The team learned from these issues: “Each unexpected issue on the aircraft has been ‘good news’,” said Robin. “There’s been…bad things, but also good news, because when on a subject…we didn’t think about, and Safran didn’t think about, that means that there was something real [to test and discover], That’s the point of making a demonstrator, to be in real life and not making only Powerpoints.

“We had some integration issues about the harness,” he continued. “It seems easy to install [an electrical distribution] harness with 800 volts in real life. [But] when you get more knowledge, [it’s] not that easy, especially when you have fuel, which is not too far away. You have to take care of all the dysfunctional cases. And we learned that some of them were probably not taken at the right level. We learned a lot on the integration of the harness.”

“We learned a lot also about the operation of high voltage aircraft,” he added, “because we are thinking design as an engineer [during] certification, but at the end of the day, well, you have an aircraft, and if you have 800-volt batteries, how you do you operate? How do the maintenance people take care of it?”

Daher + Safran + Airbus

Collaboration between the three giants was also a key takeaway: They essentially learned how to transform the relationship between airframe and powerplant OEMs as well as how to leverage the agility of start-ups that were brought into the development of the Eco-Pulse. The marketable aircraft program will depend on this coordination.

“So for the time being, we can enjoy something like 10-year periods, starting 2020 till the end of the decade, where we can focus our engineering teams on the preparation of the most disruptive technologies for the future,” said Pascal Laguerre in the media briefing. “That’s really an opportunity to make this happen. So we see this opportunity between our companies to align our goals at the same moment in time with the same mindset, the same intent, and saying, ‘Well, none of us individually can do it, can make it happen.’”

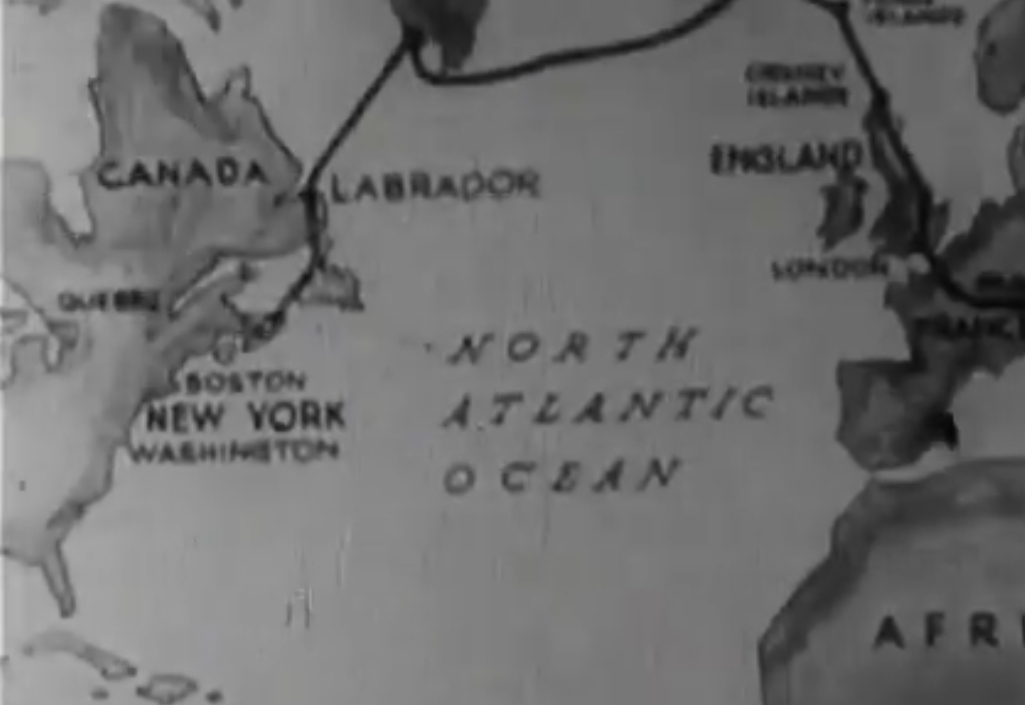

Sourcing of raw materials, including the rare earth metals needed for the batteries, from places on the globe that are not secure, is another takeaway from the program. Recycling those materials in a circular economy is vital to meeting several objectives, including those overall to support sustainable aviation. Finding other ways of approaching component construction and reuse is also critical.

What Comes Next for Daher?

The follow-on aircraft program from Daher and CORAC will be explored with a project beginning in 2025 with the goal of meeting the OEM’s objective of a go-to-market aircraft plan by 2027. With the real flight testing of Eco-Pulse, the goals are transformed beyond “the paper” according to Robin: “We have now a better idea of what the maturity is of the technological bricks [that] we can put inside an aircraft. We will launch next year a new CORAC project with Safran, in order to work on these hybridization and electrical technologies.

“The idea is to have this assessment of the [technologies’] maturity and to be able to meet the objectives given by my CEO [Didier Kayat],” he concluded. “That’s to propose a design and manufacture aircraft by the end of this strategic plan—so by the end of 2027, we [will be] working on this more electrical aircraft.” Also, Daher’s team will determine what the benefits were of the distributed propulsion system.

We’re certainly excited to see the next project leave the hangar…